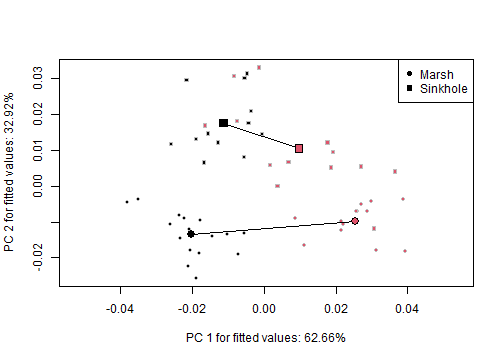

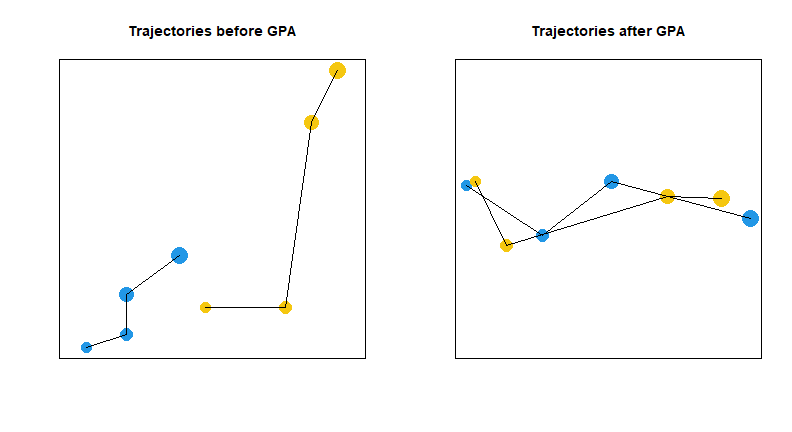

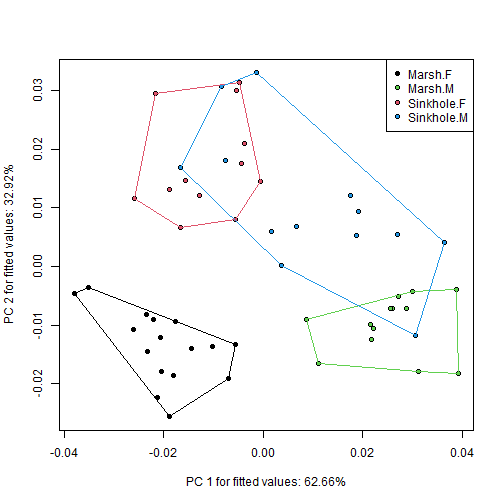

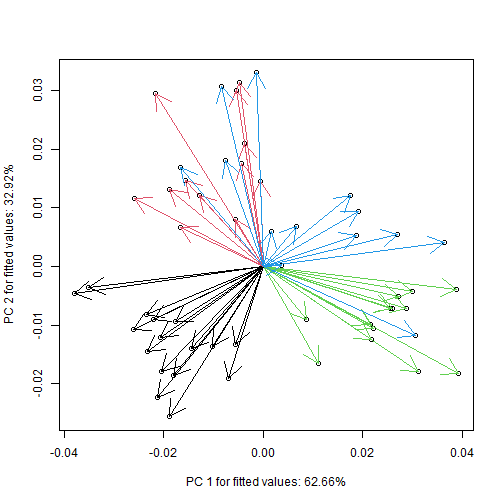

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # 11. RRPP Extensions ] .subtitle[ ## Comparison of vectors, trajectories, and morphological disparity ] .author[ ### ] --- ### Overview: + Secondary RRPP statistics + Trajectory analysis + Comparison of shape vectors + Comparison of shape trajectories + Morphological disparity + Comparison of shape variances --- .center[ # Part I. RRPP Secondary Statistics ## (Don't let the name imply they are worse than primary statistics. They are probably better!) ] --- + RRPP is useful for providing `\(P\)`-values and `\(Z\)`-scores for **.blue[primary statistics]**, like `\(F\)`, `\(R^2\)`, `\(\lambda_{Roy}\)`, etc. + These may be typical test statistics or descriptive test statistics (like `\(R^2\)`) that can be used as test statistics. + They are calculated directly from `\(\mathbf{S}\)` or `\(\hat{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\)` matrices. + RRPP is rather essential for statistical evaluation of **.green[secondary statistics]**, which are statistics calculated from other statistics. These involve contrasting variances, or contrasting differences between estimated values, or finding the angular differences between vectors that describe the differences between estimated values, plus other. + Think of the `pupfish` example. + Sexual dimorphism is a vector that describes the difference between male and female means, within consideration of fish sampled from one population. + This vector could be tested in term of its length, `\(d\)`, to determine if males and females have different shapes. + But what if we wish to entertain whether the difference in one population is the same as the difference in the other population. We need to be able to contrast the differences (one statistic) in a secondary statistic. ***Secondary statistics make use of primary statistics for better hypotheses.*** + Because we have many (thousands) of `\(\mathbf{S}\)` and `\(\hat{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\)` matrices after RRPP, we have commensurate opportunity to test many hypotheses. --- .center[ # Part II. Trajectory analysis ## Using RRPP to compare attributes of shape change ] --- ### From Factorial Models to Trajectories .pull-left[ We have seen that factorial models enable us to attribute variation to differing factors, and in the case of categorical factors, determine whether levels (groups) differ in some way. For instance, the plot below shows 4 groups which appear distinct in their trait attributes. However, as biologists, we have additional information about these groups; for instance, they may be males and females from each of two populations. Thus, levels of one factor `sex` are really *linked* via the other factor `population`. ] .pull-right[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/IntroPCPlot.png" width="1252" /> ] --- ### RRPP secondary statistics ### From Factorial Models to Trajectories .pull-left[ We have seen that factorial models enable us to attribute variation to differing factors, and in the case of categorical factors, determine whether levels (groups) differ in some way. For instance, the plot below shows 4 groups which appear distinct in their trait attributes. However, as biologists, we have additional information about these groups; for instance, they may be males and females from each of two populations. Thus, levels of one factor `sex` are really *linked* via the other factor `population`. ] .pull-right[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/IntroPCPlot2.png" width="1252" /> ] .pull-left[ Might there be additional information we could glean statistically from viewing these as linked data (trajectories)? ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis .pull-left[ Trajectory analysis is a means of quantifying and comparing attributes of these linkages. In the case below, the vectors linking males and females form sexual dimorphism vectors. These represent *vectors of change* in trait values between levels (the sexes in this case), and these may be treated as a secondary dataset that may be compared across populations. Trajectory analysis accomplishes this task. ] .pull.right[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/IntroPCPlot2.png" width="50%" /> ] .footnote[ Vector and Trajectory Methods Discussed Today were Originally Described in: Collyer and Adams. *Ecology*. 2007; Adams and Collyer. *Evolution*. 2007; Adams and Collyer. *Evolution*. 2009; Collyer and Adams. *Hystrix*. 2013. ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis In the case of **factorial** models, one might consider two orders of possible factor-level analyses: Order | Vectors | Test :---- | :------- | :------------------------------------------------------ First | `\(\mathbf{\hat{z}}_i\)` | Compare means, given appropriate null (reduced) model, to ascertain a logical explanation for significant factor interactions. (*We have done this already. e.g., pairwise comparisons.*) Second | `\(\mathbf{\hat{z}}_i - \mathbf{\hat{z}}_j\)` | Compare change in means across levels of factor B among levels of factor A. secondary analyses target the pattern of change and analyze the geometric attributes of trajectories that describe the change. As an example, with the pupfish body shape data, a first-order analysis seeks to understand if the variation among the means of the `sex:population` groups was meaningful, after accounting for general population differences and sexual dimorphism. A secondary analysis might define sexual dimorphism vectors and compare their geometric attributes in a specific way, to help explain *why* the variation is meaningful. --- ### Interaction Terms in Linear Models Let's take a step back and reconsider model interaction terms. Say we have `Z ~ A + B + A:B`. The interaction term `A:B` measures the joint effect of main effects `A` & `B`. It identifies whether responses to `A` dependent on level of `B` Interactions are Are *VERY* common in biology. For instance, the example below shows 2 species in 2 environments (Factors `A` & `B`). Species 1 has a higher growth rate in the moist environment, while species 2 has a higher growth rate in the dry environment. Statistically, such patterns would be identified by a significant `species:environment` interaction. <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/TradeOff.png" width="50%" /> ##### Note: the study of trade-offs and reaction norms in evolutionary ecology is essentially the study of interactions! --- ### Understanding Interactions Significant interactions identify a joint response of factors (response to Factor `B` depends on level in Factor `A`) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/TradeOff.png" width="50%" /> Interpreting interactions for univariate data is straightforward: simply plot them! <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/Interaction-UnivData.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Understanding Interactions (Cont.) For two traits, more complicated variants are possible, but a 2D plot still suffices for visual inspection. <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/Interaction-BivarData.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Interactions to Trajectories In the previous plots, we have 'linked' levels of one factor across another. For two levels, that produces vectors, whose patterns we compared visually. More formally, we should use quantitative summaries. Consider the following: .pull-left[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta3d.png" width="3161" /> ] .pull-right[ These represent **Change Vectors** describing the difference in mean trait values between levels within each group. For our previous model, `coords ~ population + sex + population:sex`, they could represent vectors describing the sexual dimorphism within each population. The question then is: do these vectors differ, and if so how? ] --- ### Attributes of Change Vectors (2-Point Trajectories) Once we have defined the change vectors for each group, we require summary measures of them. In any dimension, vectors have two attributes: a **length** and a **direction**. First, the length of each change vector is found as: `\(\small d_1 = \Vert \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1\Vert=\left( \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}_1} \right)^{1/2}\)`. Where: `\(\small{\mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1}=\mathbf{\hat{z}}_{1,2}^T - \mathbf{\hat{z}}_{1,1}^T\)`. This is the length of `\(\small{d}_1\)`. Vector lengths are obtained for all vectors. Next, we calculate two test statistics: one that describes the difference in vector magnitudes, and another the difference in their angular direction: `$$\small MD = \lvert d_1 - d_2 \rvert = \left| \left( \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}_1} \right)^{1/2} - \left(\mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_2^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_2 \right)^{1/2} \right|$$` `$$\small\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_2 }{d_1d_2}\right)$$` Here, `\(\small{MD}\)` represents the *magnitude difference* between vector lengths, and `\(\small\theta\)` represents the *angular difference* between vector directions. --- ### Hypothesis Tests Evaluating `\(\small{MD}\)` and `\(\small\theta\)` involves something we have performed previously RRPP with factorial models. The procedure is as follows, and is based on a comparison of variation from `\(\mathbf{X}_F\)` & `\(\mathbf{X}_R\)` where: `\(\mathbf{X}_F\)` is: `Z ~ A + B + A:B` `\(\mathbf{X}_R\)` is: `Z ~ A + B` Estimate | `\(\small\mathbf{X}_{R}\)`| `\(\small\mathbf{X}_{F}\)` :------------- | :------------------- | :-------------------------- Coefficients | `\(\tiny\hat{\mathbf{\beta_R}}=\left ( \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_R^{T} \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_R\right )^{-1}\left ( \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_R^{T} \mathbf{\tilde{Z}}\right )\)` | `\(\tiny\hat{\mathbf{\beta_F}}=\left ( \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_F^{T} \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_F\right )^{-1}\left ( \mathbf{\tilde{X}}_F^{T} \mathbf{\tilde{Z}}\right )\)` Transformed Fitted Values | `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{Z}}_R=\mathbf{\tilde{H}}_R\mathbf{\tilde{Z}}\)` | `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{Z}}_F=\mathbf{\tilde{H}}_F\mathbf{\tilde{Z}}\)` Model Transformed Residuals | `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{\tilde{E}}}_R=\mathbf{\tilde{Z}}-\hat{\mathbf{Y}}_R\)` | `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{\tilde{E}}}_F=\mathbf{\tilde{Z}}-\hat{\mathbf{Y}}_F\)` For `\(\mathbf{X}_F\)`, `\(\small{MD}\)` and `\(\small\theta\)` are obtained from `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{Z}}_F\)`. Then: - 1) RRPP is performed by permuting in every random permutation `\(\small\hat{\mathbf{\tilde{E}}}_R\)` - 2) pseudo values are obtained as `\(\small\mathbf{\mathcal{Z}} = \mathbf{\hat{Z}}_{R} + \mathbf{\tilde{E}}_{R}^*\)` - 3) Full model coefficients and fitted values estimated for `\(\small\mathbf{\mathcal{Z}}\)` - 4) `\(\small{MD}_{Rand}\)` and `\(\small\theta_{Rand}\)` are calculated for least-squares means --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Comments Testing `\(\small{MD}\)` and `\(\small\theta\)` evaluates *context dependent* trait changes. "Is there greater sexual dimorphism in one population as compared to another?" This is based on vector attributes, which embody aspects of interaction terms. In fact, RRPP used in this manner is explicitly a test of **interaction term** attributes (think of the RRPP procedure we utilized: `Z ~ A + B + A:B` versus `Z ~ A + B`). In fact, if the interaction term from the manova is not significant, this implies that there is no context-dependent pattern in the data: understanding the main effects in the model is sufficient. Note also, that standard pairwise comparisons 'leave some information on the table' that vector analysis evaluates. Pairwise comparisons are at best tests of magnitude between two groups. They do *NOT* evaluate differences in distances between pairs of groups, nor directional differences. **Only trajectory/vector analysis accomplishes this!** --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Familiar Example What we have not yet established is whether secondary statistics generated by RRPP are appropriate (they are). We will examine that shortly, but let's first get a sense how this works. This example uses the `R` package, `geomorph` with the `Pupfish` data from `RRPP`. .med[ ``` r data(Pupfish) fit <- lm.rrpp(coords ~ Pop * Sex, data = Pupfish, iter = 999, print.progress = FALSE) TA <- trajectory.analysis(fit, groups = Pupfish$Pop, traj.pts = Pupfish$Sex) ``` ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Familiar Example (Cont.) Summaries of `\(\small{MD}\)` and `\(\small\theta\)` .pull-left[.med[ ``` r summary(TA, attribute = "MD") ``` ``` ## ## Trajectory analysis ## ## 1000 permutations. ## ## Points projected onto trajectory PCs ## ## Trajectories: ## Trajectories hidden (use show.trajectories = TRUE to view) ## ## Observed path distances by group ## ## Marsh Sinkhole ## 0.04611590 0.02568508 ## ## Pairwise absolute differences in path distances, plus statistics ## d UCL (95%) Z Pr > d ## Marsh:Sinkhole 0.02043082 0.01282538 2.661595 0.001 ``` ]] .pull-right[.med[ ``` r ### Correlations (angles) between trajectories summary(TA, attribute = "TC", angle.type = "deg") ``` ``` ## ## Trajectory analysis ## ## 1000 permutations. ## ## Points projected onto trajectory PCs ## ## Trajectories: ## Trajectories hidden (use show.trajectories = TRUE to view) ## ## Pairwise correlations between trajectories, plus statistics ## r angle UCL (95%) Z Pr > angle ## Marsh:Sinkhole 0.7393716 42.32209 23.55561 3.635082 0.001 ``` ]] --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Familiar Example (Cont.) And a plot of the patterns: .pull-left[.med[ ``` r TP <- plot(TA, pch = as.numeric(Pupfish$Pop) + 20, bg = as.numeric(Pupfish$Sex), cex = 0.7, col = "gray") add.trajectories(TP, traj.pch = c(21, 22), start.bg = 1, end.bg = 2) legend("topright", levels(Pupfish$Pop), pch = c(21, 22), pt.bg = 1) ``` The trajectory analysis and plot demonstrate that sexual dimorphism differs between the two populations. One population (Marsh) displays greater SD than the other. Also, the direction of that sexual dimorphism is not the same in the data space. ]] .pull-right[.med[ <!-- --> ]] --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Example 2 .pull-left[ Another example in salamanders, regarding evolutionary phenotypic responses of two species to competition (design: 2 species in 2 environments). Here, the magnitude of vectors was not different but the direction was. The interpretation in this case is that both species displayed similar *amounts* of phenotypic evolution in response to competition, but the direction differed. In this case, the species diverged evolutionarily: a pattern consistent with character displacement. ] .pull-right[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide02.png" width="1920" /> ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis With Covariates .pull-left[ Earlier examples of trajectory analysis assumed no covariate, visually: <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/TrajNoCov.png" width="936" /> However, for many hypotheses, one must account for variation due to a covariate while simultaneously assessing patterns of multivariate change. ] .pull-right[ Adams and Collyer *Evolution* (2007) demonstrated that simply incorporating the covariate into the model permitted accomplishes this analytical goal. <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/TrajWithCov.png" width="871" /> This is the linear model: `Z ~ cov + A + B + A:B`. ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis With Covariates (Cont.) The method works exactly as expected! .pull-left[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta.wcov.png" width="90%" /> ] .pull-right[ + Character change along a gradient, 3 scenarios: + No character displacement (CD) + Asymmetric character displacement + Symmetric character displacement + This approach correctly identifies CD when it is present, and does not identify it when it is not present ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Generalizations Now we have to consider that a trajectory might contain more than two points. Two-point trajectories are great because they have two attributes - length and direction - with which we have learned how to handle for statistical tests. A three point trajectory is a sequence of two vectors; a four-point trajectory is a sequence of three vectors; etc. We could go crazy trying to analyze every pairwise vector of every pairwise difference in a pairwise fashion, or further consider the attributes of trajectories. <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide04.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Generalizations Trajectories have as attributes 1. **Length** (of a vector between two points, of the sum of vector lengths - the **path distance** if three or more points) 2. **Direction** (angular change from a reference, of vectors for two points, or of first PCs for three or more points) 3. **Shape** (if three or more points, the cumulative angular and length changes of consecutive vectors) .center[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide04.png" width="60%" /> ] --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) .center[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide04.png" width="30%" /> ] Trajectory Statistics Attribute Compared | 2-point Statistic | >2-point Statistic :-------- | :----------- | :------------------------------------ Length | `\(MD = \mid {d}_1 - {d}_2 \mid\)` | `\(MD = \mid \sum d_1 - \sum d_2 \mid\)` Angle | `\(\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_2 }{d_1d_2}\right)\)` | `\(\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\mathbf{v}_{1,1}^T \mathbf{v}_{2,1}\right)\)`, where `\(\mathbf{v}_{i,1}\)` refers to the first eigenvector of the `\(i^{th}\)` group, which happens to already be unit size. Shape | *NA* | `\(D_P = \left(\left( \mathbf{\gamma}_1 - \mathbf{\gamma}_2 \right)^T \left( \mathbf{\gamma}_1 - \mathbf{\gamma}_2 \right) \right)^{1/2}\)`, where `\(\mathbf{\gamma}\)` is a vectorized form of the matrix of trajectory points, which has been centered, "standardized" by matrix size, and rotated. `\(D_P\)` is Procrustes distance. --- ### Generalized Procrustes Analysis **Using trajectories as shapes, which in fact they are.** .center[ <!-- --> ] --- ### Generalized Procrustes Analysis (Cont.) .center[ <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide04.png" width="30%" /> ] Trajectory Statistics Attribute Compared | 2-point Statistic | >2-point Statistic :-------- | :----------- | :------------------------------------ Length | `\(MD = \mid {d}_1 - {d}_2 \mid\)` | `\(MD = \mid \sum d_1 - \sum d_2 \mid\)` Angle | `\(\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_1^T \mathbf{\Delta \hat{z}}_2 }{d_1d_2}\right)\)` | `\(\theta = \cos^{-1}\left(\mathbf{v}_{1,1}^T \mathbf{v}_{2,1}\right)\)`, where `\(\mathbf{u}_{i,1}\)` refers to the first eigenvector of the `\(i^{th}\)` group, which happens to already be unit size. Shape | *NA* | `\(D_P = \left(\left( \mathbf{\gamma}_1 - \mathbf{\gamma}_2 \right)^T \left( \mathbf{\gamma}_1 - \mathbf{\gamma}_2 \right) \right)^{1/2}\)`, where `\(\mathbf{\gamma}\)` is a vectorized form of the matrix of trajectory points, which has been centered, "standardized" by matrix size, and rotated. `\(D_P\)` is Procrustes distance. --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) Each of these statistics could be considered test statistics in a hypothesis test. The expected value of each is 0 under a null hypothesis of no difference in geometric attribute. The question now is whether these secondary statistics behave as we would hope for hypothesis tests. The way to test this is to create data with known properties and see what happens. --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide08.png" width="70%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide09.png" width="70%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide10.png" width="70%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide11.png" width="70%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide12.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/pta/Slide13.png" width="70%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis (Cont.) **Conclusion: Using RRPP, trajectory analysis provides appropriate pairwise test statistics.** - The intention for performing trajectory analysis should be clear. The statistics can be more useful than simple pairwise comparisons, especially if there are several groups and multiples "stages" in the trajectories. The many pairwise combinations would become exhausting to consider. - Although the models have to be factorial in nature, they can include covariates or other factors, in which case the points are least squares means. - An example will illustrate how this analysis is effective with more than two points. --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Illustrative Example <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/snake.pta/Slide1.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Illustrative Example <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/snake.pta/Slide2.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Illustrative Example <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/snake.pta/Slide3.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Illustrative Example <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/snake.pta/Slide4.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide1.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide2.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide3.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide4.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide5.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide6.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/ta.examples/Slide7.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Examples of Its Use in The Scientific Literature A review in *Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.* (2018) highly recommends use of trajectory analysis for evaluating patterns of parallel and non-parallel evolution. <img src="LectureData/11.RRPPExtensions/Bolnick.png" width="100%" /> --- ### Trajectory Analysis: Summary and Other Comments - There are many different research questions where comparing trajectories in multivariate data spaces is appropriate. - Many E & E research designs are factorial by nature. - Related to the theme of high-dimensional data analysis, none of these test statistics are variable-number dependent. Any number of dimensions is fine. - Trajectory analysis provides a path forward to examine patterns not possible by the 'standard toolkit'. RRPP is the workhorse that makes it possible to use biologically intuitive statistics. --- ### Morphological Disparity: How do we measure it? .center[ <img src="LectureData/07.groupdifferences/dispersion.png" width="90%" /> ] --- ### Morphological Disparity: How do we measure it? .pull-left[ The simplest way to measure morphological disparity for data landmark data (or any data) is to calculate the squared distances of residuals from fitted values of a linear model `\(\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{\epsilon}_i^T\mathbf{\epsilon}_i\)` - If the model has means, the residuals are vectors sprouting from their means - If the model has vectors to describe patterns of covariation (slopes), the residuals are vectors surrounding fitted values along a slope trajectory. ] .pull-right[ .center[ <img src="LectureData/07.groupdifferences/dispersion.png" width="1920" /> ] However, if we want compare disparity among groups, it makes more sense to average it, if groups have different sizes. `$$PV = n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{\epsilon}_i^T\mathbf{\epsilon}_i = n^{-1}trace\left( \mathbf{EE}^T\right)$$` ] --- ### Disparity is Variance `$$PV = n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{\epsilon}_i^T\mathbf{\epsilon}_i$$` That's right. The simplest measure of disparity is variance. The smaller the variance the more clustered points are to their estimate; the larger the variance the more diffuse. Like everything else we have considered thus far, measuring variance for the sake of measuring it, is not that appealing. Comparing variances is. Note that this form of variance divides by `\(n\)`, not degrees of freedom. We are not interested in estimating a population parameter from variability in a sample. If we called this *mean disparity* instead of variance, maybe it would make more sense. --- ### Disparity is Variance (Cont.) How does one test a null hypothesis about variance? The simplest way to establish a null hypothesis is, `$$H_0 : \left| \sigma_1^2 - \sigma_2^2 \right| = 0$$` `$$H_A: \left| \sigma_1^2 - \sigma_2^2 \right| > 0$$` And for such a test -- and this is important -- the residuals **ARE THE DATA**. Steps for a pairwise test of variances: 1. Obtain residuals, let these be the data 2. Fit the linear model, `\(\epsilon \sim \mathbf{X}_g\)`, where `\(_g\)` indicates the factors describe groups. 3. Find the pairwise distances among means. 4. Perform RRPP with a reduced model with only an intercept (same as just randomly shuffling residuals among groups) - Repeat steps 2-3 in each permutation 5. Obtain the usual statistics ( `\(Z\)` and `\(P\)`-value) from the empirically-generated sampling distributions. --- ### Disparity: Example #### Example Data Set: 'pupfish' #### Objective: To determine if shape disparity differs among population:sex groups --- ### Disparity: Example .pull-left[.med[ ``` r library(geomorph) data("pupfish") pupfish$Group <- interaction(pupfish$Pop, pupfish$Sex) fit <- procD.lm(coords ~ Pop * Sex, data = pupfish, print.progress = FALSE) ``` ``` r P <- plot(fit, type = "PC", pch = 21, bg = pupfish$Group) shapeHulls(P, pupfish$Group, group.cols = c(1,3,2,4)) legend("topright", as.character(unique(pupfish$Group)), pch = 21, pt.bg = c(1,3,2,4)) ``` ]] .pull-right[.med[ <!-- --> ]] --- ### Disparity: Example (cont.) #### Analysis option 1 .med[ ``` r PW <- pairwise(fit, groups = pupfish$Group, print.progress = FALSE) summary(PW, test = "var") ``` ``` ## ## Pairwise comparisons ## ## Groups: Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## ## RRPP: 1000 permutations ## ## ## Observed variances by group ## ## Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## 0.0003439300 0.0005803226 0.0003607052 0.0008318581 ## ## Pairwise distances between variances, plus statistics ## d UCL (95%) Z Pr > d ## Marsh.F:Sinkhole.F 2.363925e-04 0.0002473769 1.518166 0.053 ## Marsh.F:Marsh.M 1.677513e-05 0.0002492051 -1.346688 0.902 ## Marsh.F:Sinkhole.M 4.879280e-04 0.0002412492 3.180101 0.001 ## Sinkhole.F:Marsh.M 2.196174e-04 0.0002806646 1.160169 0.130 ## Sinkhole.F:Sinkhole.M 2.515355e-04 0.0002726187 1.441515 0.075 ## Marsh.M:Sinkhole.M 4.711529e-04 0.0002662683 2.741881 0.002 ``` ] --- ### Disparity: Example (cont.) #### Analysis option 2 .pull-left[ .med[ ``` r MD <- morphol.disparity(fit, print.progress = FALSE) summary(MD) ``` ] .small[ ``` ## ## *** Attempting to define groups from terms in the model fit. If results are peculiar, define groups precisely and check model formula.) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## morphol.disparity(f1 = fit, print.progress = FALSE) ## ## ## ## Randomized Residual Permutation Procedure Used ## 1000 Permutations ## ## Procrustes variances for defined groups ## Marsh.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.F Sinkhole.M ## 0.0003439300 0.0003607052 0.0005803226 0.0008318581 ## ## ## Pairwise absolute differences between variances ## Marsh.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.F Sinkhole.M ## Marsh.F 0.000000e+00 1.677513e-05 0.0002363925 0.0004879280 ## Marsh.M 1.677513e-05 0.000000e+00 0.0002196174 0.0004711529 ## Sinkhole.F 2.363925e-04 2.196174e-04 0.0000000000 0.0002515355 ## Sinkhole.M 4.879280e-04 4.711529e-04 0.0002515355 0.0000000000 ## ## ## P-Values ## Marsh.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.F Sinkhole.M ## Marsh.F 1.000 0.902 0.053 0.001 ## Marsh.M 0.902 1.000 0.130 0.002 ## Sinkhole.F 0.053 0.130 1.000 0.075 ## Sinkhole.M 0.001 0.002 0.075 1.000 ``` ]] .pull.right[ Sinkhole males had significantly greater shape disparity than the Marsh fish, but not sinkhole females. <img src="11-RRPPExtensions_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-49-1.png" width="30%" /> ] --- ### Foote's Partial Disparity `\(^1\)` Foote (1993) proposed that the total disparity of a sample comprises partial disparities of inherent groups (e.g., clades). One can also calculate and compare these. Total disparity .med[ ``` r fit0 <- procD.lm(coords ~ 1, data = pupfish, print.progress = FALSE) MD.tot <- morphol.disparity(fit0) ``` ``` ## No factor in formula or model terms from which to define groups. ## Procrustes variance: ## 0.001043201 ``` ] .footnote[1. Foote. *Paleobiology* 1993.] --- ### Foote's Partial Disparity (cont.) Foote (1993) proposed that the total disparity of a sample comprises partial disparities of inherent groups (e.g., clades). One can also calculate and compare these. Partial disparity `$$pPV = (N-1)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{\epsilon}_i^T\mathbf{\epsilon}_i$$` where `\(N = \sum{n_i}\)` --- ### Foote's Partial Disparity (cont.) #### Fractional parts of the whole <!-- --> --- ### Foote's Partial Disparity (cont.) #### Analysis .pull-left[ .med[ ``` r MD.part <- morphol.disparity(fit0, groups = pupfish$Group, partial = TRUE, print.progress = FALSE) summary(MD.part) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## morphol.disparity(f1 = fit0, groups = pupfish$Group, partial = TRUE, ## print.progress = FALSE) ## ## ## ## Randomized Residual Permutation Procedure Used ## 1000 Permutations ## ## Procrustes variances for defined groups; partial variances (disparities) were calculated. ## Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## 0.0002824902 0.0002372006 0.0002761654 0.0002670281 ## ## Proportion of total disparity for each group: ## Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## 0.2657770 0.2231669 0.2598264 0.2512297 ## ## ## Pairwise absolute differences between variances ## Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## Marsh.F 0.000000e+00 4.528958e-05 6.324846e-06 1.546211e-05 ## Sinkhole.F 4.528958e-05 0.000000e+00 3.896474e-05 2.982747e-05 ## Marsh.M 6.324846e-06 3.896474e-05 0.000000e+00 9.137263e-06 ## Sinkhole.M 1.546211e-05 2.982747e-05 9.137263e-06 0.000000e+00 ## ## ## P-Values ## Marsh.F Sinkhole.F Marsh.M Sinkhole.M ## Marsh.F 1.000 0.745 0.943 0.883 ## Sinkhole.F 0.745 1.000 0.420 0.532 ## Marsh.M 0.943 0.420 1.000 0.846 ## Sinkhole.M 0.883 0.532 0.846 1.000 ``` ]] .pull-right[ Important points: - Partial disparities are measured from grand mean; must have an intercept model - Degrees of freedom are bias-corrected, because the total sample disparity is an estimate of true morphological disparity ] --- ### Disparity: Other descriptive statistics There are a few other descriptive statistics that one might come across, linked to disparity or data dispersion. These have not been really explored with regard to high-dimensional data. One thing of which to be aware, there are still several unexplored frontiers for high-dimensional data. Analysis of disparity is one of those frontiers. We are loathe to offer hypothesis test suggestions, using descriptive statistics as test statistics, without sound theoretical research to validate them. Chief among the developmental unknowns is appropriate null models for these: - Nearest neighbor distance (a measure of a tendency for data to cluster rather than be diffuse) + For each point find the shortest vector to the next point, then find the mean or standard deviation for a group - Convex body volume (the volume of a data space represented by a group) + This is extremely difficult to do in many dimensions. - Eccentricity (a measure of departure from spherical scatter) + Measured as `\(1 -\frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1}\)` after performing a singular value decomposition (or eigen analysis) on `\(var = n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{E}_i^T\mathbf{E}_i\)`. Additionally, these statistics are likely rather sample size-dependent. None of them seem sensible for small samples. --- ### Disparity: Other descriptive statistics (Cont.) - Eccentricity (a measure of departure from spherical scatter) + Measured as `\(1 -\frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1}\)` after performing a singular value decomposition (or eigen analysis) on `\(var = n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{E}_i^T\mathbf{E}_i\)`. <img src="LectureData//11.RRPPExtensions/eccentricity.png" width="80%" /> --- ### Disparity: Other descriptive statistics (Cont.) However, even as descriptive statistics, they can be sometimes useful. Here is a figure that appears in Adams and Collyer (2018) `\(^1\)`, after receiving harsh criticism from a reviewer (in early rounds), stating that RRPP does not produce appropriate covariance matrices, as expected from a Wishart distribution. .center[ <img src="LectureData/07.groupdifferences/wishart.png" width="70%" /> ] .footnote[1. Adams and Collyer. *Syst Biol.* (2018)] --- ### Disparity: Other descriptive statistics (Cont.) .center[ <img src="LectureData/07.groupdifferences/wishart.png" width="70%" /> ] Measuring eccentricity for 100 experiments of 1,000 RRPP generation of covariance matrices, each, we actually found that RRPP generated a more spherical distribution (disparity) of covariance matrices than sampling from a Wishart distribution (a multivariate sampling distribution for covariance matrices). It exceeded theoretical expectation! --- ### Morphological Disparity: Summary and Other Comments - Analyzing disparity as opposed (or in addition) to mean differences adds an interesting dimension to shape analyses - One has to be careful to match the statistic to research question - Comparison of group dispersion + PV (or other distance-based stats) + CHA/CHV = amount of shape space, including outliers + ECC = anisotropy, covariation of “subshapes” - **Because RRPP allows analysis of secondary statistics, use of different statistics to measure disparity could be easily implemented.** --- ### Additional Literature (not all shape data) Note that these references tend to have earlier references within: - Bookstein, F. L. (1991) Morphometric tools for landmark data - Foote, M. (1993) Contributions of individual taxa to overall morphological diversity. Paleobiology. 19:403-419. - Layman, C. A., et al. (2007) Can stable isotope ratios provide for community-wide measures of trophic structure? Ecology 88: 42-48. - Turner, T. F, et al. (2010) A general hypothesis-testing framework for stable isotope ratios in ecological studies. Ecology: 91: 2227-2233.